Meaning, belonging and incentives

I didn't get where I am today by being right about things

It was during the height of the anti-Trump hysteria when I tried an experiment on Twitter. Was it really the case that a lie travels half way around the world before the truth gets its boots on. Of course it is and proving it was slightly chilling. But profitable.

My tribe was convinced that 'the Russians' had craftily engineered Britain's rejection of European Union membership and gone on to install Donald Trump as the leader of the free world.

It wasn’t true. But the story opened up some great personal opportunities and I ended up doing quite well from it.

I noticed that talking about 'disinformation' was a popular way of gaining two types of capital. Roughly these were reputational and social. What unfolded now seems quite funny, but at the time I sincerely believed that I had something to offer in the good fight against an other side who were making stuff up all the time, while my cohort was taking a valiant stand for truth.

No regrets. I got some paid journalism gigs out of it, interviewed some interesting people and ended up delivering the keynote at an international conference exploring the future of democracy (earning a surprisingly large fee).1

Reflecting on my story is useful in making sense of all the nonsense I see in public discourse today.

By public discourse I mean the conversations that take place between strangers online and the 'reporting' and commentary that is fed to us from corporate and independent media.

Hypothesis: it's mostly all about meaning, belonging and incentives.

But we tend to think it's really about right and wrong. Truth versus fiction. Fact versus error.

I first learned this one January afternoon in 2017.

I was infuriated by a particular Twitter account which presented as a pro-Trump black woman. I was so steeped in the fiction of a Putin-controlled POTUS that I couldn't believe that any black women supported Donald Trump.2 Therefore this black woman had to be ... a bot.

We were all obsessed with bots in the online world. Fake personas created en masse to create a flood of content and sentiment that suggests a consensus that is desired by someone shady.

To be clear, this does happen and it has a long and inglorious tradition ranging from dirty energy companies faking popularity for their latest environmentally harmful project to low-rent marketing operations trying to drum up a buzz around a fad health drink.

We're vulnerable to this kind of rubbish, as a species, due to our herding instinct. In future stories I'll focus on some of my favourite examples of this, such as how unknown music with many apparent downloads is much more likely to be downloaded than something of equally unknown status that appears to have been ignored by everyone else. Be honest. When you're on Amazon you're more likely to buy a product that has thousands of reviews (even when you know that a lot of those reviews aren't real) than one that has none because ... safety in numbers.

I haven’t read the book, but this quote resonates

Herding has become another costly junk behaviour that overrides rational analysis in a world in which sham popularity can be manufactured - Jim Rubens 'OverSuccess'

So it happens. But it also doesn't happen and we still think it's happening when we are so siloed away from other people's views that we can't believe they are real people.

So it was with my black Trump supporter. So I made up a story about her.

Pulling an image from Google Streetview of a Moscow suburb and selecting a less cliched male Russian name than Sergei I concocted a quick story about how I'd discovered that 'Deplorable Melissa' was really a Russian agent.

That tweet thread was my first experience of virality and even before I'd managed to get to the bit where I confessed that it was all made up, the retweets and replies were coming in faster than I was used to. And the chilling aspect was that very few people were reading the whole story before sharing it. So you had a story which a little further on explicitly stated that it was fake news and people were already breathless in their condemnation of the Russians.

I was out of the trap. I'd proved how susceptible we are to the kind of stories that we want to be true.

I knew my audience, though. And I was still blindly accepting of the Russiagate narrative, so I went on to assure them that there really are countless Russian bots promoting Trump3 and that all I was really saying was that this one wasn't.

When I found my story again, to make sure I was recounting it correctly for this piece, the urge to delete my entire Twitter history was strong. It's shameful. But instructive.

It's a monument to meaning, belonging and incentives.

Looking back at the period that began in 2016 and the Brexit referendum it's clear that 'fighting' (it's always this word, isn't it - 'fighting') for my side's values brought meaning into my life. Suddenly I really knew who I was. Which was the kind of person who stands up for good things and is against bad things. After a lifetime of left wing instincts and voting I was able to consolidate that position as part of my identity.4

A sense of belonging seemed to flow from this. Knowing for certain (not for long, as it would turn out) that I knew who my tribe was felt good. As a natural 'outsider' I wasn't really used to this. The closest I'd ever got to a sense of belonging would be at music gigs. The more obscure the music, the more belonging I felt in a crowd of fellow aficionados. But there were a lot more people concerned about Brexit and Trump than with enjoying The Olivia Tremor Control or Neutral Milk Hotel in Sheffield, so being heralded as a 'disinformation expert' during febrile times, with thousands of strangers becoming interested in what I thought about stuff was gratifying.

As it happens, I didn't belong at all. My tribe turned out to be a mirror image of their enemies and I began to notice that we were largely (but unawarely for the most part) more concerned with losing our status than actually standing up for 'right'. As ever, there'll be more to expand on this theme in future stories.

The incentive I felt was that exposure of the kind I was successfully generating paid off. Literally. Being mouthy on Twitter brought me lucrative work, including one contract that was entirely unrelated to culture or politics. I just kept popping up in the feed of someone who remembered me from corporate days and he hired me to help launch a business.

I see these incentives everywhere, underlying almost everything that seems to be wrong about our information environment. There's a reasonably interesting YouTuber who has reasonably interesting guests who is now focused more than he has to be on extremely fringe views about climate change (not happening, not a problem, not caused by humans etc) and I can see why he's doing that. When you can get 442,000 views in one month by interviewing a consultant to the fossil fuel industry, who claims falsely to be a co-founder of Greenpeace, about how wrong all the climate science is, that's an incentive.

There's a reason that so much news and commentary is so partial and that's the incentive to please your audience with more of what they already think. Balanced information is boring when there are feelings to be had. There's a reason why so much behaviour on social media is awful and it's partly down to the incentive to be seen. And to belong. When you're 'fighting' on behalf of your side, you definitely belong in your side.

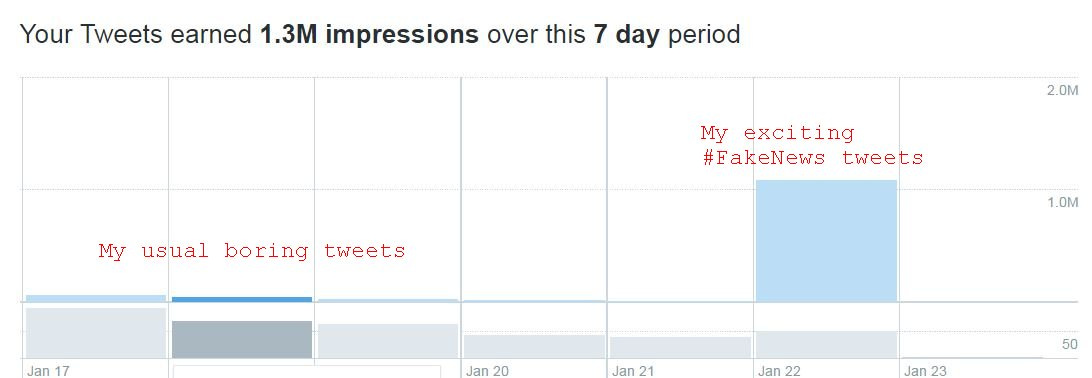

The incentive for me to make up a story about a Twitter account was this (a graph I produced shortly after the episode).

Imagine a Twitter or a Facebook where no one was able to react to posts. Imagine how interesting that might be to browse through. But imagine how strange it would be to participate, without knowing whether anyone noticed what you'd thrown into the pot. We've grown so used to the incentives of online publishing that we barely notice them and the way they shape discussions. But it's how we know one thing for certain. It's not about information for its own sake. And once you recognise this, consuming it takes on a very different flavour.

A short and momentarily depressing experience to relate.

There are few figures I despise more than a former MEP called Daniel Hannan. If you'd like to know the depths of my disdain for him you can read this. It's quite funny (especially some of the replies). It's a rolling tribute to his mendacity that I used to curate on Twitter. He is a zealot and therefore he must be wrong all the time.

Private Eye routinely dismantles him, which is one of many ticks in the box for the Eye around here.

So I'm reading a piece in Private Eye about how Hannan has said something in a paper he wrote about trade deals. And the thing he has said is that consuming lamb imported to Britain from New Zealand may have less negative impact on the environment than consuming domestic lamb. The Eye is ridiculing this statement and I'm loving it.

I text my best friend, who happens to be an academic in the field of sustainability. He knows a thing or three about environmental impact audits. He also happens to despise Hannan too. So I'm all set to celebrate some fresh reasons to believe what a prick Hannan is.

It turns out that Hannan might be right.

As they are fond of saying on the social sites, let that sink in...

(Of course, we consoled ourselves by considering that he is probably only accidentally right. Or right for the wrong reasons. But the fact is that I was unpleasantly jolted and it led to some interesting research into the topic of intellectual humility and how many of us could do with a bit more. One for the future here.)

Still uneasy about the current hype around the evils of Facebook. (Previous thoughts on this here).

OK, I get it. A huge profit-driven entity causes huge harm that literally results in daily injury and death all over the world while contributing to health problems for countless more people.

But, on the other hand, it has social benefits. Helps people to be less isolated and makes enormous contributions to economic activity. People also enjoy using its products.

Ah, but it has a terrible history of knowing how it could reduce the harms it causes while covering up the fact that it knows. Because it would be damaging to profits.

Slam dunk.

I'm talking about the car industry.

<Insert shrug emoji>

Final thought. People in my tribe were fond of labeling evidence of our inconsistency with the dismissive term 'whataboutery'.

We would never say 'actually, yes, you're right about that - we aren't really in a position to preach now you point that out'.

The point about the car industry above is an example of whataboutery.

'What about' is often a difficult question to address because it means interrogating the real reason for focusing on one thing when we would rather not. That's why the word 'whataboutery' was invented. To circumvent the need for thinking about certain challenges.

'Whataboutery' is a lazy word designed to get you off the hook, is what I'm thinking.

Here’s an interview I did at the event, Innovating Democracy, organised by the Netherlands Institute For Multi-Party Democracy. I can’t bear to watch it now. It’s not that I was wrong per se. Just that I was naive and partial in how I saw the problem of good information versus bad information https://innovatingdemocracy.io/interviews/mike-hind/

It’s interesting that I was under the impression that Trump increased his black vote in 2020. Google will throw up many stories saying this. But they are contradicted in some quarters, like here.

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2021/07/06/new-2020-voter-data-how-biden-won-how-trump-kept-the-race-close-and-what-it-tells-us-about-the-future/

There’s plenty of evidence that Russian bots were used, but little-to-no evidence that they had any impact. And the fact that there are countless bots operated by nation states the world over, to influence opinion elsewhere, is almost never mentioned by commentators in this field.

I was still under the impression that objecting to Brexit was a vaguely left wing perspective, rather than unwittingly supporting a largely ‘soft right’ project that held the seeds of Remain’s failure.

Header picture credit: Amusingly, it’s a deactivated account. Funny that.

Hi Mike, reading through your piece I thought that your are just confirming the long held thoughts I've had, so wasn't going to comment. Upon reflection I find myself with questions which you have the right to not answer and I shall respect this. Just call it my curiosity and desire to understand but in a compassionate way. You speak of things you have done previously and in my previous comments to one of your earlier posts I've spoken about identity and a need to belong. So my questions are who are you now as a person and where do you belong?

I've asked myself if I should ask these questions and concluded that the worst thing that can happen is a no response by you. I hope I am not causing offence or being too direct.