The curious case of 'Clem' and the time I led the online harassment campaign against a British Russophile pensioner

Trolling is such fun

The recent news that a 'Russiagate II' might be on the cards for next year's US presidential election surfaced the memory of this story. It’s about how I was inspired to become a genuine internet troll.

Russiagate might be the best example of a moral panic in my lifetime, having been sucked in as an eager participant.

A moral panic is kind of fun and interesting, when you're taking part. As the label suggests, a moral panic hooks straight into your intuitions about right and wrong and these intuitions have so much emotional valence they can easily override the rational mind.

There is also a kind of 'fellowship' experience to be enjoyed, acting out with other participants.

Throw in the absorbing pastime entertainment value of 'discovering' things that seem important to surface and it's easy to understand the individual and social incentives of participation.

All these factors were in play when I engaged in the relentless digital 'duffing up' of an old guy on Twitter, in an episode which took sufficiently strange turns that the story is worth relating in detail.

For context, this wasn't an isolated incident. Many people were falsely accused of being 'bots' or 'Russian agents' on social media (typically Twitter) in the years following the 2016 Russiagate moral panic, occasionally even doxxing themselves in an effort to clear their names.

There was also the ‘Russian troll’ who was really just a guy on the Isle of Wight.

The Russian troll who wasn't

You can't escape Twitter. Even if you never go there. This is the story of an unreliable claim that made its way from Twitter and into the mainstream, via an article I wrote for an anti-Brexit newspap…

Another online character who many believed was a Russian troll, but who didn't make the news, was 'Clem'. This is the story of my ridiculous role in Clem's life, at least for a while.

Introducing 'Clem'.

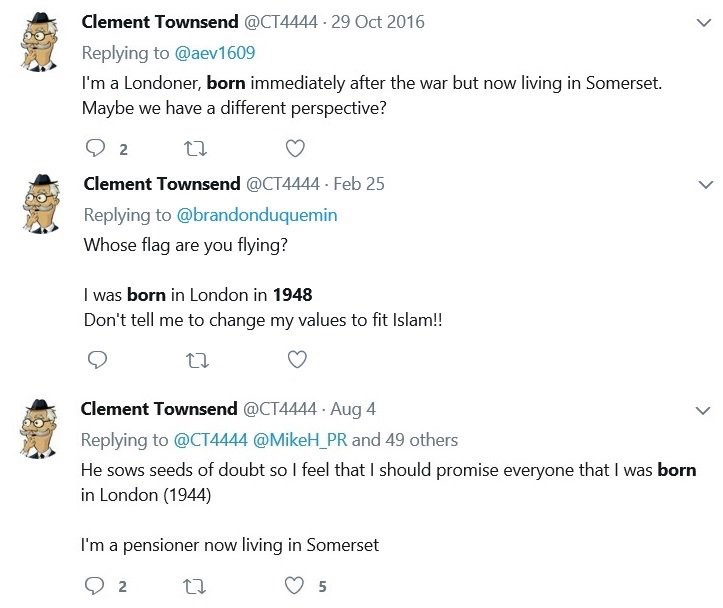

Clem identified as a pensioner, living somewhere in Somerset, UK, tweeting quite prolifically under the pseudonym of 'Clement Townsend', a 'retired strategic planner'.

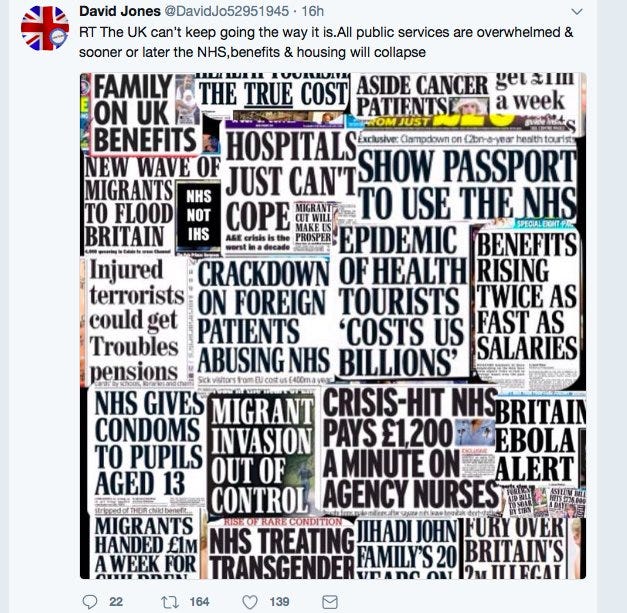

His perspectives were anti-US foreign policy, pro-Brexit and anti-EU and he invested a lot of his time in promoting the case against Russia having shot down Malaysian Airlines flight MH17.

Inevitably, all of this saw him quickly identified as a 'Russian troll'.

And so began an odd story, as me and some of my followers began to tease Clem incessantly.

It didn't help Clem that his avatar was a commonly available piece of clipart, or that his story kept changing.

We were convinced that this person did not exist, as described. This was a kind of default state for many of us who were spending too much time on Twitter, being upset and confused about how our conception of liberalism could have come under the twin attacks of Brexit and Trump. 'How's the weather in St Petersburg' became a standard riposte to any tweet that didn't follow liberal canon.

I was connected with an extremely tenacious and able online digger (who must remain nameless) who was forever discovering who many of these pseudonymous tweeters really were and privately sharing her findings with me. Invariably they were ordinary British people, of a conservative or old-school socialist bent. What they always had in common was insufficient hatred or fear of Russia, for our tastes.

But, at this point, I was convinced that Clem was a Russian state agent.

Once you have your theory, it often seems that every piece of ‘evidence’ - however circumstantial - serves to push you further into the same rabbit hole.

A funny example of this was when, using the Tor browser to access the ‘dark web’ I found Clem’s Twitter handle - @CT4444 - among 75,000 account handles listed on a document hosted on a server in Belize. Any ‘remainers’ reading this will instantly recognise the significance of Belize as a connection with Brexit. Andy Wigmore, one of the most prominent campaigners for Brexit was British-Belizean. The Leave.EU campaign - for which he was the comms lead - was constantly suspected of being Kremlin-linked (it wasn’t).

Investigation of some of these 75,000 Twitter accounts revealed that many were dormant or obviously automated (Twitter bots) and that many others had been suspended from the platform.

None of this proved anything about Clem. But I thought it must be significant. Being in the grip of Russiagate fever was like that.

Even an innocuous tweet about his lunch plans seemed the sort of thing a Russian agent who wanted to look like a British pensioner would say. (I’m laughing as I write this).

So I continued to jack Clem’s brain at every opportunity, ably assisted by a growing follower base. He got pretty mad about it. With the perspective of distance, now, he had every right to be mad at this person relentlessly trolling him. I told him I was an agent of George Soros, making a fortune from tweeting about him, and I regularly invented ridiculous stories about who Clem really was. My followers were highly entertained by this.

Then all the silly banter with Clem took a slightly sinister turn.