The most satisfying work ever

Telling the most interesting story yet, after a lifetime of writing

A year ago this piece marked the start of something that has become the best story I've ever told.

It's what people call a 'passion project'. There’s probably no money in it. It will never really be finished. There will always be more to learn. It seems important. And I love doing it.

On June 21 1944 the inhabitants of the town where I now live were going about their day. But something had changed.

St Pierre Eglise was suddenly empty of Germans and Georgians.1

After four years of ordering everyone around, taking all the best food, building ugly concrete installations and doing what occupying forces do in a quiet bucolic paradise the invaders were gone.

Hitler had ordered Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben to defend the nearby port of Cherbourg at all costs (as the Führer was wont to do) and all the occupying forces in the Val-de-Saire were falling back to do that.

The town I refer to fondly as ‘Cherbs’ was now 'Fortress Cherbourg' and the recently arrived allies wanted it badly. Since June 6 they had been landing vast quantities of men and equipment on beaches, just a little way down the coast and they needed a deepwater port to build their forces for the breakout into deeper France

Around lunchtime an American jeep sped through the town square and out the other side of St Pierre Eglise. The Americans were expected because everyone knew that the allies were on their way. But it was the first moment that anyone in St Pierre saw them.

A few minutes went by and the jeep returned, this time more slowly. It pulled up in the square and 4 GIs found themselves mobbed by excited locals.

I don't know who those first men were. But I’ll find out eventually. I’m always obsessed with minutiae.

The men were from reconnaissance Troop A, of the 24th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized.

The moment I learned this I was surprised to have never heard of them.

Then I was pretty bugged about it.

The irritation stemmed from finding out that they went on to essentially take the same journey in 1944 and 1945 - facing all the same dangers, fighting many of the same battles and losing just as many men - as the legendary Easy Company, immortalised by Band of Brothers.

Easy Company were part of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, whereas Troop A were part of a 'mechanized cavalry group'. Different jobs, same journey.

Being a complete rookie in military history I had no idea what ‘cavalry’ even meant in WW2. And I started out assuming that a reconnaissance unit just goes around looking at things, getting intelligence and reporting back.

But that was only a small part of the job. Most of the time the work was fighting, albeit in specialised roles. If it had mostly been about observing and finding out, many more of the guys from Troop A - and the other four troops that made up the 24th Cav Recon - would have eventually made it home again.

The job of a reconnaissance troop in the US army of 1944/45 was full-on.

For example, in 'mechanized cavalry' a typical mission is to go up against what you already know is a superior enemy force so that you draw them out. You withdraw only when the resulting fight threatens your annihilation and the units that are actually designed to take on the forces you're fighting take over to finish the job.

I'm not exaggerating. From my research it's clear that they were often analogous to pawns going up against knights and bishops, day after day.

Except these were pawns with outsize cojones.

Those huge balls swung from a ragtag mix of professional officers and ordinary guys.

I have come to love those guys.

Let me introduce you to some.

This is Captain Brooks Ogden Norman, who commanded the reconnaissance unit from which those men first arrived in my town.

A warrior, who seems to have embraced danger at every opportunity, including when there was no actual fighting. He went on to fight in Korea and Vietnam. His son tells me that he was 'a bit of a wildman' and a joker. He was one of those characters that you might call a ruffler of feathers.

Appearances can be deceptive, though.

I have a letter written by Brooks Norman, to the mother of one of his best friends, Joe Gresham. Joe was killed by a rifle round to the head in a tiny hamlet near me. In the letter he describes retrieving Joe's body personally from the nothing place of Gonneville. And how it was the first time he had cried since childhood.

The letter was sent from a hospital, where he was recovering from his second or third wounding in 1944 (it's still unclear how many times Brooks Ogden Norman was wounded).

Then there is Captain William M. Kober.

Bill Kober commanded the squadron's medical detachment. The documents I have about that make grim reading.

Crawling around in mud, snow, battlefield detritus and worse to retrieve the wounded. Under enemy fire. Treating civilians. Helping German casualties too, which they resented at times - but that was the job and their duty of honour under the Geneva Convention.

The medical detachment was permanently under-manned and their vehicles unsuited to the work. Unheated, for example. They often faced the logistical nightmare of being part of a rapid advance which was constantly leaving the field hospitals far to the rear.

Bill died in France. It was August 1944. A German patrol infiltrated the squadron's positions by night and destroyed his halftrack ambulance with an anti-tank weapon. It was clearly marked as a medical vehicle.

That's what the war was like. It was vile and ugly. People on all sides did terrible things. Some of 'my guys' did regrettable things too.

It's easy to judge people when you aren't in their shoes and I do a bit less of it, since pursuing this research.

Bill’s son Mike still has his his dad's spurs. They're from the time when cavalry were still on horseback - which was right up until 1943. Mike remembers the day on base when the new tanks, armoured cars and jeeps arrived and the men handed their horses in with a special ceremony. Mike was seven years old when he lost his dad.

Here’s Captain Elliott Averett Jr, who took command of light tank Company F, when his predecessor was wounded.

Elliott too would be wounded. Then he would discharge himself - against the wishes of the doctors in the field hospital - and make his way back to find his men. Because that's what men like Elliott did.

However tough you know war to be, try multiplying it by a factor of n, where n is a large integer, and then try imagining what it takes to keep volunteering yourself like that.

Elliott Averett Jr was a keen photographer, so we have many pictures previously unseen outside the family, covering his entire journey from training in Britain to becoming part of the military government forces occupying Germany.

Although it is often stirring there is nothing romantic about the story I'm uncovering.

War turns ordinary people into a shadow of their normal selves.

One 19 year-old Company F trooper (not Elliott, I should point out) breezily describes, in a letter home to mom and pop, how a surrendering German they had neither the time nor the inclination to capture continued appealing for help after they shot him several times. He only stopped his annoying cries when they ran their tank over him.

You read the daily 'After Action Reports' and come to understand what life was like in the squadron. Sometimes there was no time to take prisoners. Often there was no food to give to prisoners.2 And if you left them to their own devices they would probably kill more of your buddies. Yes, it's bad what he did. And that's all I can find to say about it. It haunted him in his old age.

Doing this work I often wonder what modern media, with all its simplistic moral clarity, would have made of the realities of total war, rather than the localised conflicts we know today.

Here's Corporal Mike Arendec.

Mike was a postal worker, in Ohio. He did clerical work and delivered the mail for the squadron.

One day, just a short time after D Day, the squadron liberated a little town down the road from me called Quettehou. Mike took it on himself to go back to the field HQ to see if there was any post.

This was the front line two weeks after the start of the biggest invasion operation in history, but Mike had a job to do and a lot of friends who loved receiving letters from home.

On the way back he came under fire and his jeep ended up in a ditch, with Mike nursing a broken nose.

He was retrieved, along with the mail, a short while later.

From correspondence I’ve seen from 50 years later, his commanding officer Brooks Norman (see ‘wildman’ above) evidently thought this was hilarious.

Aged 36, Mike Arendec was a larger than life character. And apparently a stellar poker player. He claimed to have sent thousands of dollars home from his winnings. Everyone evidently loved him.

You'll smile to know that Mike survived the war.

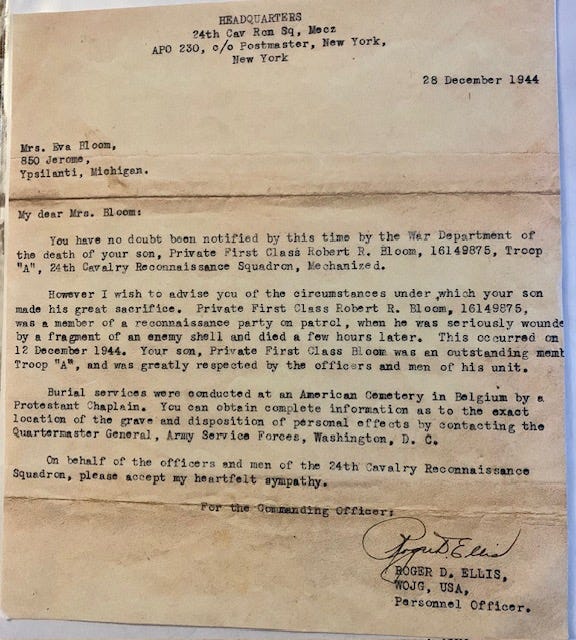

Unlike Private Robert R. Bloom.

Bobby Bloom was already dead when his mother received the Christmas card he sent her in 1944.

This arrived before the card.

On and on this story unfolds, each day.

I'm constantly amazed when a family we (I have a great team of volunteer helpers now - you can see them on the website) have traced are so happy to help with photographs, stories and souvenirs of their fathers, grandfathers and uncles.

They are glad that someone is finally telling this story. They keep thanking me for being interested and I'm running out of ways to say that it feels like I have little choice in the matter because I love it and I can’t stop now, anyway.

Someone has to tell this story. It seems unjust to me that the 24th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized, was consigned to the status of barely even a footnote in the liberation of Europe.

They earned a Croix de Guerre (a major medal awarded by the French state) for a battle in which they lost several men, clearing yet another nowhere hamlet 20 minutes from where I'm writing. I've been there and the locals I asked had never heard of the squadron who lost six men there. They just know that it was some Americans who liberated Bourg de Lestre and that's it.

The squadron deserves its place in history.

Only last year a book came out that recounts in often minute detail the D Day operation and the eventual breakout from Normandy. I read it. There is no mention of the squadron. There is an appendix which promises to give a minute-by-minute account of D Day itself. The squadron isn't mentioned in that, either.

And yet, two men of the squadron were among the first four seaborne allied soldiers onto French soil. They swam from a rubber dinghy onto an island, off Utah Beach, to secure it several hours before the landings began. They waved their colleagues ashore and at least one was killed that day by a landmine and several were injured by enemy artillery.

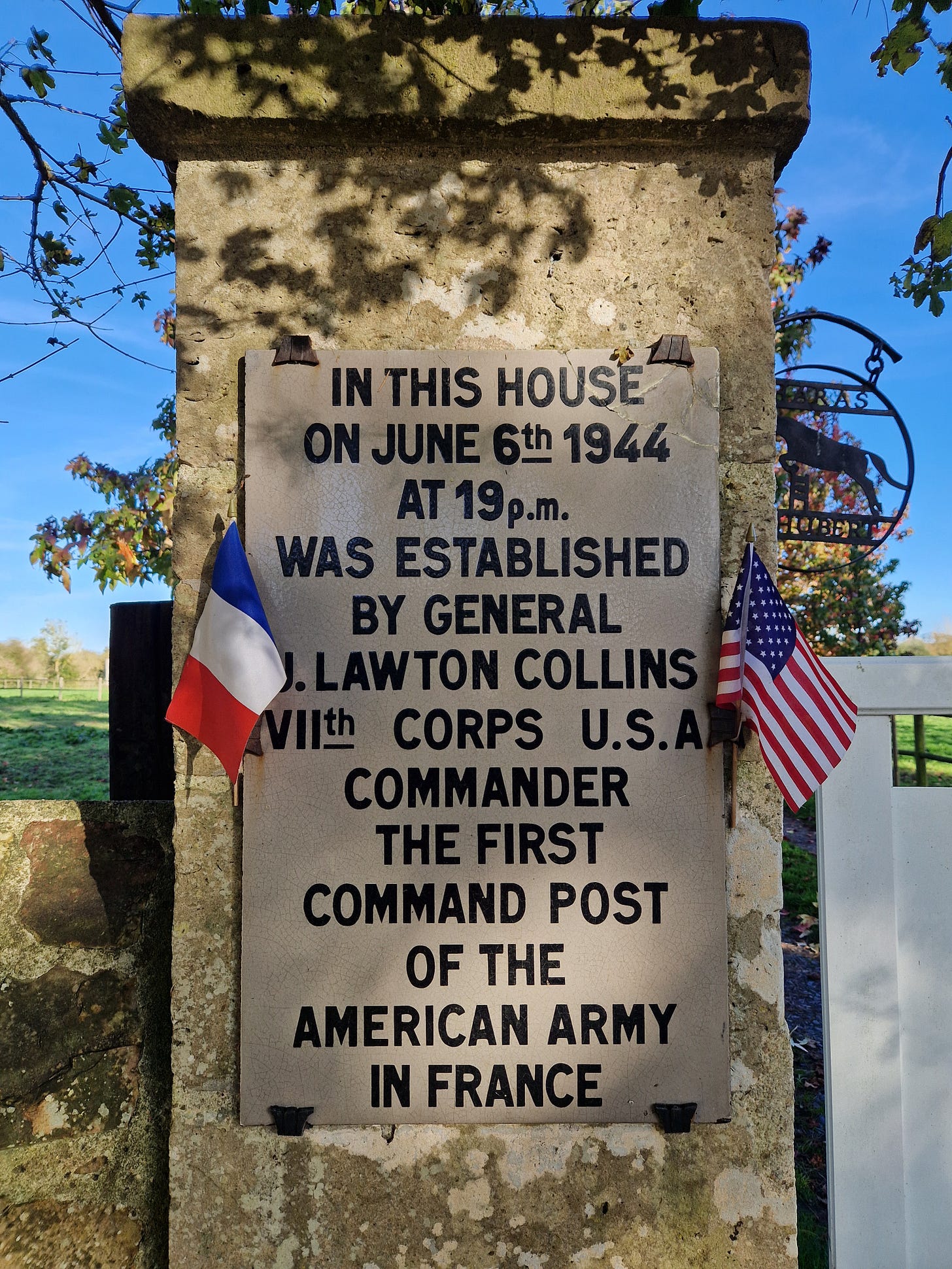

Then they came onto the mainland to provide security for the first headquarters established by General ‘Lightning’ Joe Lawton Collins, while most of the rest of the allies’ forces were still landing.

The squadron was a real player in the liberation of Europe. This wasn’t a bit part. There are hundreds of unsung units like this that don't get films made about them. I just happen to have chosen one of them, because there was a personal geographic connection.

Now it feels very personal.

I'll be going to the reunion of the squadron's regiment later this year, in South Dakota, to meet more families and research some things. If I can afford the air fares.

Sadly, as far as I have been able to tell so far, none of the men from the squadron are alive today. And their sons and daughters are getting old too, now. The project is something of a race against time.

As I write this, an email just appeared. It's from the nephew of a guy who served in reconnaissance Troop C.

It's typical of the vibe.

I'm constantly reminded that this project isn't just about privations and killing. There is often a strand of reconciliation running through the story. One of the guys from Troop A married a German woman. And today his son is also married to a German woman who I chat with on WhatsApp now about nothing in particular.

Today's email is from the nephew of a 'Tec 4' (a rank that denotes some kind of specialist skill) called George Sweep.

In it are these lines.

"George hated the Germans ... when other troopers would give chocolate to German children, he refused. He could only see those children growing up to kill American soldiers. That hatred passed with George. I have been host to four German exchange students and I count them and their parents among my best friends"

I'm a sucker for that kind of thing. Redemption and human connection arising from all of that misery.

Perhaps because I have an ordinary journalistic background I still hold to the principle that great stories are about people, rather than things.

I did worry a bit at first that I would become one of those gnarly old guys who knows all the minutiae about uniforms and which bullets were manufactured in which years once I became genuinely interested in that war. Obsessed with the detail.

But actually, while I'm deriving a lot of pleasure from the technical learning, I'm mostly loving the connections that come with it. There are people over in the US who feel more like friends to me now than volunteer research assistants or just veteran family contacts. We talk all the time. I know them now, not just what happened to some of their relatives.

One of my best friends here now is Yann, a local guy who was interested in the squadron long before I even heard of them. Yann is a major supporter of this work, both financially and as an expert in the field.

And the more connections I make, the more real the men I'm researching seem to become.

At first I thought it was going to be a military history website and (eventually) a book, dispassionately relating the squadron's movements and actions. But that isn't really my style.

We have a Signal group chat for the various people who are now helping with the project. Sometimes there are mad discussions about the features of a particular piece of equipment as my nerdy friends figure out when and where one of the hundreds of battlefield photographs we now have was taken. I love all that.

But really, for me, it's all about telling the stories of the people who came over here from over there and did what they did. These remarkable people, many of whom started out as completely unremarkable until the US decided that enough was enough and Hitler needed sorting out.

George Sweep (the armoured car driver mentioned above) joined the cavalry, instead of any other unit, because he loved horses. How human is that. And then the cavalry got mechanized and he was ‘mounted’ in an M8 Greyhound instead of on an Arabian Remount.

When they went home again (the fortunate ones) they did things like factory assembly work, wholesale ice cream delivery and farming. Mike Arendec went back to being a mail man.

One of them, who did two of the most insanely brave things I've ever heard about, married a film actress and ran advertising for cosmetics giants like Max Factor. This was him.

Here's another man.

Donald W. Coffey was initially left for dead, when an artillery shell decapitated the guy with whom he was carrying a heavy box. He only lived to tell the tale because he swore at the medics who pronounced him too far gone.

Today his son says he never once heard his father swear. That's how bad it must have been in those moments for Donald, with his back and abdomen filled with burning hot shrapnel.

I get emotional doing this research. Some of it is excitement as new stories or souvenirs of the men emerge and some of it is sadness, because many of the stories are unspeakably awful.

The stout guy standing to the left in this picture was a much-loved officer. Albert Cecil Sauerman. He fell to his death from a 14th floor hotel bathroom window, in the middle of the night. Albert had been wounded and ‘terminally discharged’ from the army. It was recorded as an accidental death.

They're often called The Greatest Generation and they probably were. But they weren't machines. I've lost count of the sons and daughters who tell me that they now see that their fathers showed all the symptoms we know today as PTSD.

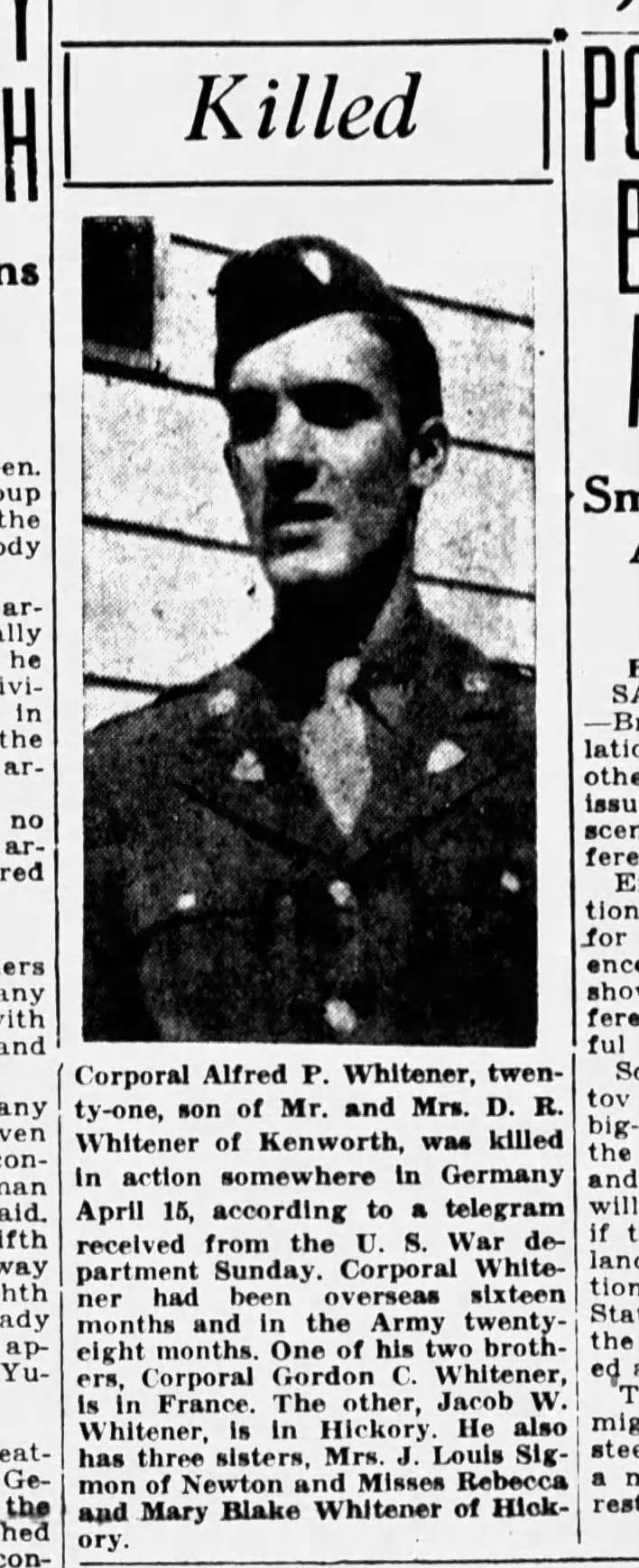

This is Bill Stephens. He made a pact with his best friend, in reconnaissance Troop B, that if anything happened to either of them the other would visit their family after the war.

That duty would ultimately fall to Bill, because he lost his best friend in Germany just a few weeks before the war ended. Today his son Del says that if he ever pressed dad on his wartime experiences, Bill would either clam up or cry.

His friend was Alfred P. Whitener. He died, aged 21, less than a month before Germany’s unconditional surrender.

I'm writing this on a TGV, speeding up the middle of France on my way home, surrounded by French people speaking French and enjoying their own culture. Things might have been quite different today without all those men who came here. Like Bill Stephens, Mike Arendec, Brooks Norman, Barrett Dillow, William Kober, Elliott Averett Jr, Bobby Bloom, Alfred Whitener, George Sweep and the hundreds of other guys who will get a page on the website to say you are not forgotten.

It's hard not to have personal favourites when you start feeling close to your subject.

One of mine is Joe Negri, of reconnaissance Troop A.

We're lucky that Joe was one of the few who did talk about the war. Not because he liked any of it, but he knew that it would all be forgotten at the individual level if men like him didn't speak.

Here's Joe. He’s on the right, standing with Mike Arendec. Joe was actually Guiseppe, but changed his name - as an Italian in New York - to fit in.

Joes's daughter is now on the volunteer research team, having provided a trove of written and recorded memoirs from her dad.

You can hear Joe recalling some of his moments on the battlefield on the website. His page is here.

If you ever practice intentional gratitude this will make sense. I’m constantly grateful that I wasn’t in the squadron.

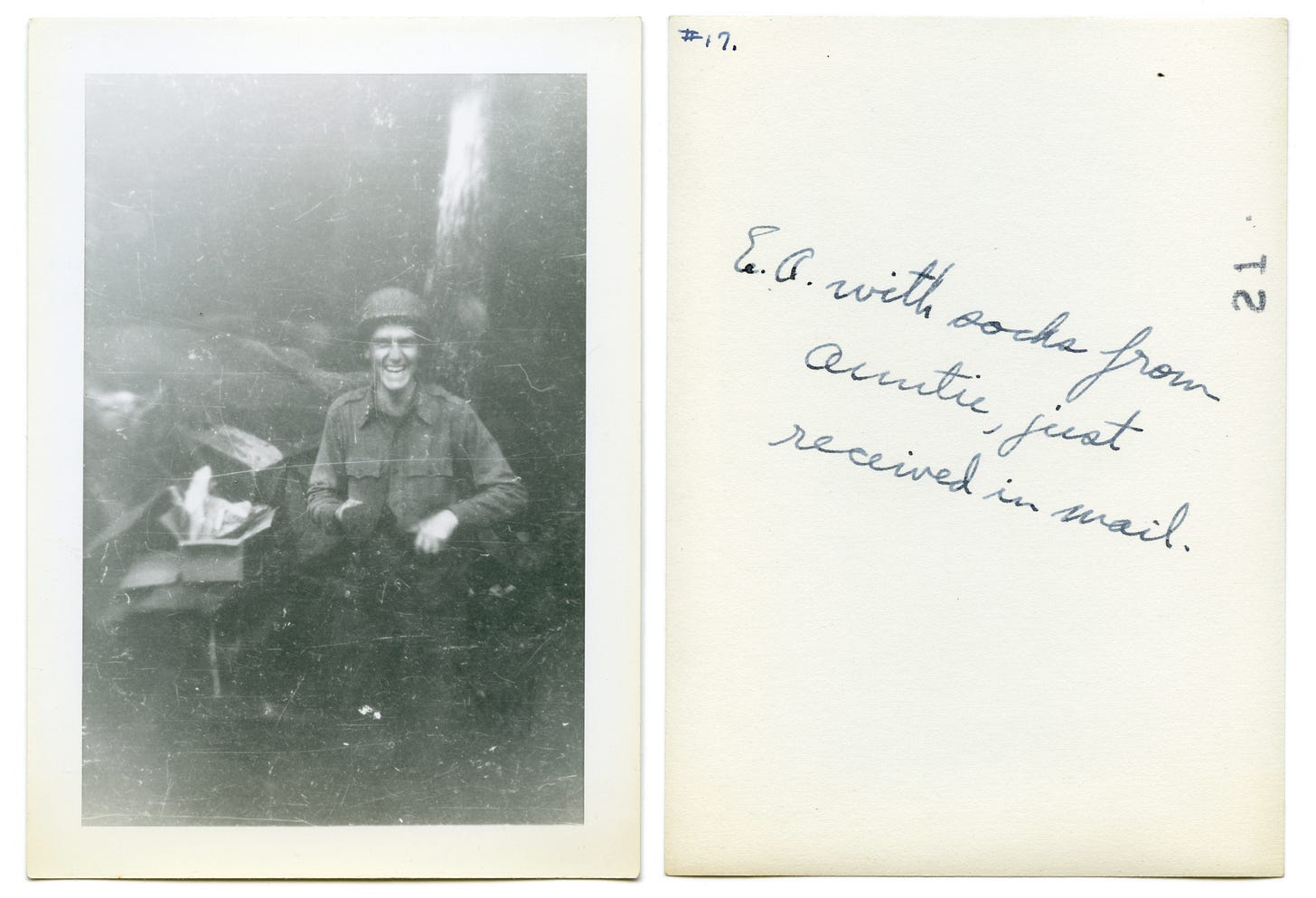

Remember the last time you got new socks? How great did you feel?

You probably weren't as thrilled as Elliott Averett Jr of Tank Company F was in this photograph, taken on December 1 1944, in Germany.

It is captioned: "EA with socks from auntie, just received in mail".

This was in the Hurtgen Forest, widely understood now as the most grisly and costly experience the US Army endured in Europe, in WW2.

That smile is a lesson to us all.

I've read a few books and watched some films about the war. Like everyone, I've been riveted by Band of Brothers. But my favourite stories now are those recounted by Joe Negri.

Let's conclude with one of his tales, exactly as he wrote it.

A Big Joe

Norm Weinburger and I were on a machine gun outpost in the Hurtgen Forest in Germany. We quietly dug out a slit trench and set up our guns on the crest of a hill, about 200 yards from our command post. After about an hour, we got hungry. Norm asked me if I would go back and make him one of my famous sandwiches. A little flattery goes a long way with me. I had cheese from K rations, a can of bacon from my C rations and bread cooked over a little gasoline burner. “Viola! A Big Joe!”.

As I was crawling back to the Command Post, our position came under an artillery barrage. The first shell hit the tree next to our slit trench. Norm was hit immediately. Then I heard the dreaded familiar, “I’m hit, I’m hit!” I jump under a tank to wait it out. Tree bursts are the worst. They spray shrapnel down on you. After the shelling was over, we grabbed a G.I. blanket and crawled up to Norm to drag him back to the Command Post. I looked at his wound and noticed he was hit in the groin area. We got him to the medics quickly. On the way back, I stumbled onto another buddy, Jackalewski. He tells me he is dying because he was spitting up blood. I tried to convince him it was just a concussion from the artillery. We got him to the medics. I never saw him after that, I hope he survived.

As it turned out, Norm spent three months back in England recuperating. After his ‘vacation,’ we welcomed him back. In fact, we invited him to accompany us on a patrol probing enemy lines. I hated patrols with a passion. But that’s what the Cavalry was used for then. Well, we met a German patrol that was doing the same thing, and we had a fire fight. Norman came out of it with a souvenir, a bullet hole in his helmet, right above his forehead creasing his helmet liner. When I caught up with him, his mouth was agape, and his face was so ashen it was gray. I patted him on the back and yelled “Welcome back Norm!”

On the way back home, we laughed about our adventures. He was so grateful that the bullet wasn’t one inch lower, and he wasn’t circumcised… twice.

All of Joe's stories are like this. His daughter too believes her dad suffered from PTSD for the rest of his life.

So that's the project to commemorate the service of the 24th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, Mechanized, after just a year.

Sometimes I close the Substack and news apps, telling me how terrible modern life is, and trawl through the hundreds of records I have detailing how shit life can really be.

All the cliches apply about gratitude for these men's service, the ones who died, had their lives changed by injury or the rest of their day-to-day lives interrupted by terrible memories.

It's good to be here in Normandy, each year, to see firsthand that the locals still care about what was done to restore their freedom.

My town of St Pierre Eglise did the squadron's memory proud for the 80th anniversary last year. At last there is a plaque in the square where those exhausted Troop A guys first rolled in.

I helped the Mayor's team a bit with the commemoration and enjoyed hanging out with the special guests who drove over from the massive US air base in Ramstein, Germany.

Of course I had moist eyes and shivers when the mayor mentioned Lt. Col. Frederick Harold Gaston Jr, who led the squadron, because it has all become so personal.

Fred Gaston Jr was a West Point graduate. A professional soldier who also deplored war.

Where would we be without men like him? Who knows. I might not even be living in this charming rural backwater on the Cotentin Peninsula if he and his men hadn't come here first. It certainly would not have been the same place that it is today.

Editorial note: this is the last free post for a while. Subscriber growth has stalled and I want to give supporters something back, which means exclusive access to what they help me to produce. Special thanks to all those people who have renewed their subscriptions. I promise some spicy stuff over the next few pieces. From next time it’s paywall city around here.

Around here the German forces were a mix that included many ‘Ostruppen’ - soldiers captured on the eastern front who had often been coerced into fighting in preference to being shot, or worked to death in labour camps.

Although the D Day invasion and subsequent breakout was an unqualified success, going in hot pursuit of the Germans across France at such pace meant sometimes outrunning your supplies. Even winning can be hard.

Mike, This entire piece was both engrossing and moving. I almost skipped it but because you wrote it thought I should give it a glance and then read every word -- some of it twice. Even had a tear or two for people I never met and about which I never thought. That is powerful writing. Thanks for doing this.

Amazing project!